Bugula neritina Linnaeus, 1758

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Bryozoa

- Class: Gymnolaemata

- Order: Cheilostomata

- Suborder: Anasca

- Family: Bugulidae

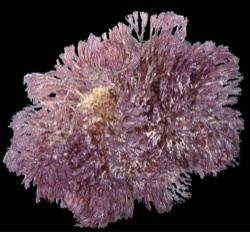

Bugula neritina is a colonial animal that grows in upright, bushy, branching tufts, up to 15 cm or so in height, that are often mistaken for a seaweed. They are usually a dark red-purple or purple-brown, though occasionally they are a dull, dark red. Some of the details described below can be seen with a hand lens; others require a microscope.

The individuals in a colony are called zooids. They consist of soft parts, called the polypide, enclosed in a rigid box, called the zooecium (Greek for "animal house"). Each branch in the colony is made up of a double row of zooecia, with all the zooecia facing in the same direction. The zooecia are stacked end-to-end, one above another, within each row. The two rows in a branch are staggered, so that the top of one zooecium comes to about the middle of the one next to it.

A single zooecium is 0.2-0.3 mm wide and 0.6-1.1 mm long. Its front is a flexible membrane, and it bears no spines, although the upper, outer corner of the zooecium is sharpened to a point. Other species of Bugula bear distinctive, bird-head shaped structures with a jaw-like element that opens and closes, which are called avicularia; but Bugula neritina has none.

Bugula neritina zooids are hermaphroditic. Zooids release eggs around the middle of their lifespan but don't release sperm until near the end, thus preventing self-fertilization. Each zooid produces a single, dark-brown embryo at a time, which is brooded in a smooth, white, globular structure at the top of the zooecium, called an ovicell. The ovicells are conspicuous and often abundant, appearing as numerous small white beads concentrated in the older and more central part of a colony. When released from the ovicell, usually around dawn, the larvae have neither mouths nor digestive tracts and are incapable of feeding. They settle onto hard surfaces within about 2-10 hours, and metamophose into the adult form. Most settlement occurs in summer and fall in temperate waters, and in late fall to early spring in warmer waters. The initial zooid buds off others, which in turn bud off others, enlarging the colony. Sexual maturity is reached at 6-8 weeks, and colonies can live for over a year.

Bugula neritina feeds with 20-24 white, translucent tentacles that are arranged in a cone-shaped funnel surrounding the mouth at the head end of the polypide. This crown of tentacles is called a lophophore. The tentacles are long and relatively stiff, with cilia arrayed along their inner faces and sides. To feed, the lophophore and upper end of the polypide are pushed out of the zooecium through an opening near the top of the membranous front of the zooecium. Currents produced by the beating of the cilia carry food particles (primarily microscopic plankton) down along the tentacles to the mouth.

Bugula neritina larvae are eaten by fish, and some nudibranchs feed on adult colonies.

Bugula neritina requires salinities above 14 ppt and does not grow well below 18 ppt. It is a common member of fouling communities in harbors and bays on the Pacific Coast, from intertidal to shallow subtidal depths. It is common on dock sides, buoys, pilings and rocks, settling often on shells and sometimes on seaweeds, sea grasses, sea squirts and other bryozoans. It is a dominant fouler and mariculture pest in Hong Kong, and is common on mangrove roots, seagrasses, algae, oyster shells, pilings, floats and other structures in the Caribbean. It is sometimes abundant on vessel hulls and within ships' intake pipes.

Bugula neritina is a source of compounds called bryostatins (which may actually be synthesized by bacteria living symbiotically within the bryozoan), one of which shows promise as a cancer treatment. Recent molecular genetic work suggests that on each coast of North America Bugula neritina may actually consist of two species that differ in their bryostatin production (Davidson & Haygood 1999; McGovern & Hellberg 2003).

Similar Species

Bugula neritina is the only red or purple bryozoan on the Pacific Coast that grows in upright, bushy tufts. Other Pacific Coast species with this colony form, including several other Bugula species, are white or tan in color, usually have spines or bird's-head avicularia, and usually lack the conspicuous, globular ovicells that are characteristic of Bugula neritina. A beginning naturalist might be most likely to mistake Bugula neritina for a small red seaweed.

Native Range

Unknown, but presumably tropical or subtropical waters.

Introduction and Distribution on the Pacific Coast [with dates of first record

- Oregon: Coos Bay [reported in 1993]

- California: Humboldt Bay [collected in 1987 on the hull of a ship, and collected on marina structures in 2000], Bodega Harbor [reported in 1972], Tomales Bay [collected in 2001], San Francisco Bay [reported in 1973], Half Moon Bay [collected in 1997], Monterey Bay [reported in 1905], Elkhorn Slough [collected in 1998], Santa Barbara [collected in 2001], Channel Islands Harbor [collected in 2001], Port Hueneme [collected in 2000-01], Marina del Rey [collected in 2001], Los Angeles-Long Beach Harbors [reported in 1927], Channel Islands [reported in 1950], Huntington Harbor [collected in 2001], Newport Bay [reported in 1939], Dana Point [collected in 2001], Oceanside Harbor [collected in 2001], Mission Bay [collected in 1977-78], San Diego Bay [reported in 1946]

- Baja California: Gulf of California from Angel de la Guardia Island south [reported in 1950]

Robertson (1905), Johnson and Snook (1927), Osburn (1950), Carlton (1979), Morris et al. (1980) and Ricketts et al. (1985) reported Bugula neritina as abundant and widespread in southern California, with its northern limit in Monterey Bay. It appears to have expanded north of there only recently. It was reported in Bodega Harbor in 1972, in San Francisco Bay in 1973, in Humboldt Bay in 1987 (on the hull of a wooden ship that had spent a month in the bay, and the previous month in Oregon), in Coos Bay in 1993, in Half Moon Bay in 1997 and in Tomales Bay in 2001. It is now common at several of these sites. Reports of Bugula neritina at Friday Harbor on San Juan Island, Washington in the early 1990s remain unsubstantiated, and in any event it has not been seen there since.

In San Francisco Bay, Bugula neritina has been collected from the near the mouth of the bay to Point San Pablo in the north and Redwood Creek in the south.

Bugula neritina was first reported on the Pacific Coast ranging from southern California to Monterey Bay in 1905. It was most likely transported there in hull fouling, but since it does occur in oyster beds on the Atlantic coast, it might have been introduced in one of the few 19th century shipments of Atlantic oysters (Crassostrea virginica) to southern California.

Additional Global Distribution [with dates of first record]

Bugula neritina has a broad global distribution in temperate, subtropical and tropical waters, including the Red Sea [reported in 1909], India [reported in 1971], Japan [reported in 1960], China [reported in 1986], Hong Kong [reported in 1977], several sites around Australia [reported in Port Phillip Bay in Victoria in 1881, in South Australia in 1982, and in New South Wales in 1993], New Zealand [1949], Hawaii [collected in 1921], the Pacific coast of Mexico [reported in 1950], the Galapagos Islands [reported in 1930], the Magellanic Islands [reported in 1991], on both coasts of Panama [reported in the Canal Zone in 1930, and common on both coasts in 1971], Long Island Sound [collected in 1993], North Carolina [reported in 1940], Bermuda [reported in 1900], Florida [reported in 1947], the Tortugas Islands [collected in 1914], Puerto Rico [reported in 1940], Curacao [reported in 1927], Brazil [reported in 1937], Argentina [reported in 1943], southern England [reported in the heated effluent of power plants in 1912] and the Mediterranean Sea.

Transport to these regions and spread within them was probably accomplished primarily as hull fouling or with oyster transfers. Bugula neritina has frequently been collected from ships' hulls; and since it is highly tolerant of mercury, anti-fouling compounds based on this element would have little deterrent effect. It also attaches to oyster shells. Transport in ballast water is unlikely, since Bugula neritina, in common with other Bugula species, has coronate larvae that typically spend less than 10 hours in the plankton before settling, though transport as tiny colonies attached to floating material in ballast tanks, or as colonies attached to the sides of ballast tanks, might be possible.

Other names that have been used in the scientific literature

Sertularia neritina

Literature Sources and Additional Information

Carlton, J.T. 1979. History, Biogeography, and Ecology of the Introduced Marine and Estuarine Invertebrates of the Pacific Coast of North America. Ph. D. thesis, University of California, Davis, CA (pp. 715-716).

Cohen, A.N. and J.T. Carlton. 1995. Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in a United States Estuary: A Case Study of the Biological Invasions of the San Francisco Bay and Delta. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington DC (pp. 105-106).

Davidson, S.K. and M.G. Haygood. 1999. Identification of sibling species of the bryozoan Bugula neritina that produce different anticancer bryostatins and harbor distinct strains of the bacterial symbiont "Candidatus Endobugula sertula". Biological Bulletin 196(3): 273-280.

Johnson, M.E. and H.J. Snook. 1927. Seashore Animals of the Pacific Coast. Macmillan, New York (pp. 144-147).

McGovern, T.M. and M.E. Hellberg. 2003. Cryptic species, cryptic endosymbionts, and geographical variation in chemical defences in the bryozoan Bugula neritina. Molecular Ecology 12: 1207-1215.

Morris, R.H., D.P. Abbott and E.C. Haderlie. 1980. Intertidal Invertebrates of California. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA (pp. 96-97).

Osburn, R.C. 1950. Bryozoa of the Pacific Coast of America. Part 1, Cheilostomata-Anasca. Allan Hancock Pacific Expeditions 14(1):1-269 (pp. 154-155).

Ricketts, E.F., J. Calvin, J.W. Hedgpeth and D.W. Phillips. 1985. Between Pacific Tides, Fifth Edition. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA (p. 407).

Robertson, A. 1905. Non-incrusting Chilostomatous Bryozoa of the West Coast of North America. University of California Publications in Zoology 2(5): 235-322 (p. 266).

Websites

Bishop Museum and University of Hawaii - Guidebook of Introduced Marine

Species of Hawaii

http://www2.bishopmuseum.org/HBS/invertguide/species/bugula_neritina.htm

CSIRO Centre for Research on Introduced Marine Pests (CRIMP) - National

Introduced Marine Pest Information System (NIMPIS)

http://www.marine.csiro.au/crimp/nimpis/spSummary.asp?txa=6929

Smithsonian Marine Station at Fort Pierce - Indian River Lagoon Species Inventory

http://www.sms.si.edu/irlspec/Bugula_neriti.htm

Cryptosula pallasiana

Cryptosula pallasiana Bugula neritina

Bugula neritina  Watersipora subtorquata

Watersipora subtorquata